Chapter Ten

The Generations of the Sons of Noah

(Also Known as the Table of Nations)

10:1 These are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Sons were born to them after the flood.

This is the fourth listing of generations (Hebrew ‘tô·lē·ḏôṯ’) found in the book of Genesis, the account of the first generations after the flood. This chapter is often referred to as the “Table of Nations,” as the genealogy not only lists the names, it gives us insight on how the families migrated and dispersed from the area where the ark landed. The author splits the genealogy into three major sections, one for each son of Noah. In this chapter we once again see an unspecified but significant amount of time pass by.

It is interesting to note that there are 70 total people groups listed in this chapter (while the names are individuals, they are referenced in the text as progenitors of their family groups), with the exception of Nimrod, who takes action is an individual not a people group; he is listed under Ham, beginning with verse eight. We see fourteen families listed under Japheth, thirty under Ham, and twenty-six under Shem.

Considerations

As one would expect from the Word of God, this section gives us an accurate account of early history. There has never been any comparable listing found. This listing of settlements and historical foundations of ancient nations has been supported by archaeology. While most of the names listed can be identified with nations and people groups both in antiquity as well as nations that still exist today, many secular historical records and accounts vary significantly. Therefore, the commentary regarding the migrational directions and settlements listed under each son of Noah below is mostly based on extra-biblical research and therefore subject to revision by current archaeological findings. Due to the variations of languages, many historical accounts and records of antiquity are often interpreted by how words and names sound similar, not by precise word for word matching. What does that mean? It means that while the listing in Genesis chapter ten gives us a good understanding of how the families grew and disseminated after the flood, the precise location of where they settled is not provided in the Biblical text, requiring us to rely on secular history.

The Perpetual Onion (and a plea from the author)

Studying the Word of God has often been compared to being one big and absolutely incredible adventure. And it truly is. That should not surprise us as we should not expect anything less from our Creator and, of course, the Inventor of language. Readers and scholars alike have found the Bible to be a powerful message from God, plus it is also made differently than any other set of words ever to be placed on paper.

Made differently? Yes, the structure “below the words” is truly beyond our comprehension. Okay, I lost some of you there, so let me explain. Let me first ask you to write a few sentences or a paragraph that has the total number of words divisible by seven, the number of letters divisible by seven and the number of vowels and consonants divisible by seven. Go ahead, I’ll wait. Not so easy, is it? Thanks to scholars like Dr. Ivan Panin (1855-1942), who discovered the heptadic (sevenfold) structure of the Bible (without the aid of a computer), we know that the Bible is more complicated than a collection of stories. If anyone ever wanted to create anything similar, the structure alone would require the use of several supercomputers working for many years. The sevenfold nature of the Bible is only one of many elements that comprise its structure. The more one “scratches the surface” or uses the latest software to dig into Scripture, the more one discovers that there is even more detail beyond what has already been discovered. Somewhat akin to peeling a large onion! But in this case, one really big and never-ending onion.

Scholars and theologians have spent many a lifetime investigating and studying the Bible’s composition and structure. Often attempting to track down the answers to life’s puzzles or perhaps find that “elusive secret.” God’s Word has been dissected and placed under a microscope since the beginning of time (okay, I know there were no microscopes back then, but you get the point.) Some look to find answers (Dr. Panin became a believer as attested in his book, “The Structure of the Bible: A Proof of the Verbal Inspiration of Scripture,” published in 1891), while others look to find vindication (or errors). Regardless of the reason, we need look at an old, but wise idiom, “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater!” (Derived from a German proverb that was even quoted by Martin Luther) Which means, do not discard something invaluable when trying to get rid of something unusable or bad. We can adapt it here to mean, don’t get so involved with the inner workings of the Bible to the point you missed the message!

The Sons of Japheth

10:2 The sons of Japheth: Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech, and Tiras. 3 The sons of Gomer: Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah. 4 The sons of Javan: Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim.

The same listing can be found in 1 Chronicles 1:5-7 with only a minor variation. Due to the similarity of the names and role in humanity, it is believed that Japheth was the basis for the Greek mythological character of Iapetos, the progenitor of all mankind.[1] Gomer can be traced to the Cimmerians (and possibly the Goths), who settled north of the Black Sea in an area that is currently known as Crimea. According to Herodotus they were displaced by the Scythians[2] and settled in the area around Turkey’s Lake Van, and then due to a defeat by the Assyrians, moved on to Cappadocia and possibly to Germany, France, and Cambria (Wales).[3]

Magog is a subject of some controversy and speculation since the name appears much later in the books of Ezekiel and Revelation. In Ezekiel chapters 38 and 39 we read about a major conflict between several nations and the nation of Israel, that ultimately results in God intervening for Israel. One of the key players in that war is Magog, which is why many scholars call it the “Magog Invasion.” Since this invasion has not yet occurred in history as described by Ezekiel, it is associated with eschatology, the study of end-times. It is believed that they settled between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea (near modern-day southern Russia) and are identified by the early historian Josephus, as the Scythians.[4] Ezekiel also closely associates them with Tubal, Meshech, Gomer, and Togarmah (see Ezekiel 38:2-6). In the book of Revelation we see that Magog and Gog are involved in a battle after Satan is released from being held captive for one thousand years. The battle described reads very different than the one described in Ezekiel, likely two separate events (see Revelation 20:7-10).

The Madai are considered to be the Medes by the Caspian Sea (see 2 Kings 17:6; 18:11). Some scholars believe that a group from Madai migrated to India where the legend of Iyapeti was born (the father of the Afghans). The connection is primarily made due to the name sounding similar to Japheth’s name in Hebrew (‘yě·pěṯ’).[5]

Javan appears to be connected to the Hellenic people of Greece. The Tubals are generally associated with the Tabal of the Assyrian Inscriptions in the region of Cilicia and later south-central Anatolia (often considered to be related to the Tibareni). Some scholars connect the name to Tobolsk on the Tubol River in Siberia.

Meshech are considered to be the Mushki that are found referenced in both Assyrian and Egyptian literature. Scholars have also placed them primarily between the Black and Caspian Seas (Cilicia and Eastern Cappadocia). The historian Herodotus puts their settlement further west near Phrygia, while others place them near Moscow on the Mosilua River (Meshech is often thought to be the origin of the name Muskov, as the Hebrew for Meshech is ‘mūšak’) or towards the Moschian Mountains near Armenia.[6] Tiras is believed to be associated with Tursha one of the “Sea Peoples,” and may be related to the Tyrsenol, the Greek name for the Etruscans who ultimately migrated to Italy.

The author then lists the sons of Gomer and the sons of Javan, however there is no breakdown of the genealogy of the other sons given here, nor are they found later in 1 Chronicles 1:5-7. The three sons of Gomer are identified as Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah. The Ashkenaz have been identified with the Ashkuzai (or Ishkuza) of Assyrian texts that also reference them as being expert equestrians and archers. The Greeks referred to them as Scythians (which may conflict with other accounts as to the origin of the Scythians, see above under Magog). The prophet Jeremiah identifies them with the kingdoms of Ararat and Minni near Armenia (see Jeremiah 51:27). Others connect them to the Sakasenes (Saxons). Many Jews identify Ashkenaz with Germany, many of the Jews today in Germany are still called Ashekenaz. Concerning Riphath, Josephus identifies them as the Paphlagonians,[7] located between the Black Sea and Bythinia on the southern edge of the Black Sea (the name in 1 Chronicles 1:6 shows the name as Diphath, possibly due to a scribal error since the Hebrew letter ‘resh’ looks very similar to the Hebrew letter ‘daleth’). References to Togarmah can be found in both Hittite and Assyrian texts and are considered to have settled in Armenia and possibly Turkey and Turkistan (Asia Minor). Other Biblical references to the house of Togarmah include Ezekiel 27:14 where they traded horses and mules with Tyre, and Ezekiel 38:6 where it references them as being part of Gog’s army in the Magog invasion of Israel as mentioned above.

Javan is then listed as the father of Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim. The name Elishah is often linked to the word Hellas, the Greek name for themselves. Homer referred to them as the Eilesians. It is believed that the descendants of Tarshish migrated to Spain. There are several other Biblical references to Tarshish: 1 Kings 10:22 (source of gold, silver, ivory and exotic animals); 1 Kings 22:48-49 (destination of King Jehoshaphat’s ships); 2 Chronicles 9:21 (destination of King Solomon’s ships); Isaiah 23:1 (referring to sailing ships); Jeremiah 10:9 (source of silver); Ezekiel 27:12 (source of great wealth) and Jonah 1:3 (the destination of the vessel Jonah tried to escape on). Kittim is most often connected to Cyprus (see also Numbers 24:24; Isaiah 23:1 and Ezekiel 27:6). Undoubtedly, Dodanim is the same as Rodanim (See 1 Chronicles 1:7), probably for the same reason mentioned above for Riphath and Diphath, a scribal error. These are considered the Dodanoi of ancient Greece, the people of the Peloponnesus, located at different times in northern Greece, Macedonia, and Rhodes.[8]

10:5 From these the coastland peoples spread in their lands, each with his own language, by their clans, in their nations.

The word translated here as ‘peoples’, is the Hebrew word ‘gô·yim’,[9] which can be translated as ‘Gentiles’ (see KJV). It is a word that refers to a nation, a people group, or a country. Depending on the context of the passage, the word can be used to speak of the descendants of Abraham becoming a great nation (see Genesis 12:2) as well as a reference to a pagan or heathen nation (see Exodus 9:24). Here it is used is a reference to an undefined group of people from the line of Japheth. Are these the notorious “Sea Peoples,” found in history? Perhaps, however these people were probably marauding the coastlines several hundred years before the group known as the “Sea Peoples” were born (see below).

The reference to “each with his own language” will follow each listing of Noah’s sons, which is good evidence that the compilation of family names found in this chapter was written after the Tower of Babel incident recorded in the next chapter.

Considerations

The Sea Peoples were a seafaring confederation that are believed to have come from Asia Minor, the Aegean area, the islands of the Mediterranean Sea, or perhaps southern Europe, no one knows for sure, their origin has eluded history. Why no reference to the “Sea Peoples” in the Bible? It is a relatively new term. Joshua Mark wrote the following in an article for the Ancient History Encyclopedia website:

No ancient inscription names the coalition as "Sea Peoples" - this is a modern-day designation first coined by the French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero in c. 1881 CE. Maspero came up with the term because the ancient reports claim that these tribes came "from the sea" or from "the islands" but they never say which sea or which islands and so the Sea Peoples' origin remains unknown.[10]

History reports that they invaded many major nations and coastal cities around the Mediterranean Sea, Anatolia, Syria, Canaan, the Hittite Empire, Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Egypt. There are a number of historical documents that refer to these unidentified invaders. The reason they are mentioned here is that through many conflicts region wide (not just with this particular people group, although they are a great example) they are largely responsible for much the blending of cultures, language, and beliefs, as well as the forced moving and migration to lands further away.

The Sons of Ham

10:6 The sons of Ham: Cush, Egypt, Put, and Canaan.

In the Hebrew text the sons of Ham were ‘Kûš’ (Cush), ‘Miṣ·rǎ’·yim’ or ‘Mizraim’ (Egypt), ‘Pût’ (Put), and ‘Ḵenǎ’·’ǎn’ (Canaan). Cush is associated with Ethiopia since Cush is often mentioned in reference to Ethiopia and the upper-Nile regions (see Esther 1:1; Job 28:19; Psalms 68:31-32). Egypt is essentially the same region we know today as the nation of Egypt. Perhaps it was through the line of Egypt (Mizraim) that we see the connection between the location of Egypt and the Hamites in general (see Psalms 78:51; 105:23; 106:22). The family of Put is associated with the Putaya found in the Old Persian Inscriptions and were believed to be in North Africa including Lybia.[11] Canaan was the son of Ham that was cursed by Noah (see Genesis 9:25), the Canaanites settled in the land of Canaan, which will later be included in the Promised Land.

10:7 The sons of Cush: Seba, Havilah, Sabtah, Raamah, and Sabteca. The sons of Raamah: Sheba and Dedan.

The grandsons of Ham are listed with the except for Put. Beginning with the five sons of Cush we first see Seba, which is seemingly associated with Egypt (see Isaiah 43:3; 45:14) and is also found mentioned with Sheba, who is also listed in this verse (see Psalms 72:10). There are many similar sounding names of people groups that scholars associate with Seba, ranging from the region around Arabia to North Africa, however, their exact migration remains a mystery. The next son of Cush is Havilah, we saw this name back in Genesis 2:11, as the location known for gold that the Pishon River flowed around (the name is believed to be derived from the Hebrew ‘hôl’ and may mean “sandy area”).[12] The name is also seen later in this chapter as a son of Joktan (see verse 29), undoubtedly a different person, however, there are some scholars that believe there might be an unexplained connection. Some of the locations suggested for Havilah include the northeast coastal region of Africa, near Arabia or possibly further east to India. Sabtah is believed to be associated with Hadramaut (southern end of the Arabian Peninsula). Raamah is referenced, along with Sheba, as being traders in Ezekiel 27:22, however not much else is known. Sabteca is often associated with Nubia (south of Egypt) while some connect the name to a Phoenician king.

The sons of Raamah are probably more familiar to readers (perhaps this is why they are listed). Sheba was the home of the Queen of Sheba, the great admirer of King Solomon (see 1 Kings 10:1-13), located in southwest Arabia. Dedan is associated with the northwest region of Arabia (see Isaiah 21:13). The prophet Jeremiah connects Dedan to Edom (Esau) in Jeremiah 49:8 and Ezekiel suggests that Dedan either borders Edom or is part of Edom’s territory (see Ezekiel 25:13).

10:8 Cush fathered Nimrod; he was the first on earth to be a mighty man. 9 He was a mighty hunter before the LORD. Therefore it is said, “Like Nimrod a mighty hunter before the LORD.”

Although only mentioned two other times in the Bible (referring to the person in 1 Chronicles 1:10 and the land of Nimrod in Micah 5:6), Nimrod is one of the more notorious characters in the Bible. How so? Some scholars go as far as calling him the first world dictator. The text here may not reflect the true nature of Nimrod, a name that means ‘rebellion’. When we read these verses in English it appears to be a form of commendation, however the Hebrew text tells a different story. The phrase, “He was a mighty hunter before the LORD,” implies antagonism against and in opposition to God.[13] Nimrod was a great hunter but not only of animals but of men as well, looking for men to follow him. The Jerusalem Targum says this about Nimrod:

“He was mighty in hunting and in sin before the Lord; for he was a hunter of the sons of men in their languages. And he said to them, Leave the judgments of Shem, and adhere to the judgments of Nimrod. On this account it is said, As Nimrod the mighty, mighty in hunting and in sin before the Lord.…[14]”

10:10 The beginning of his kingdom was Babel, Erech, Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. 11 From that land he went into Assyria and built Nineveh, Rehoboth-Ir, Calah, and 12 Resen between Nineveh and Calah; that is the great city.

The Bible also records that Nimrod was a great empire builder, he started his kingdom by establishing four cities. Babel would be Babylon on the banks of the Euphrates River, which will later be the centerpiece of the Babylonian Empire. Some scholars attribute Nimrod with the building of the Tower of Babel (see Genesis 11:1-9), however there is no significant historical connection. Erech is perhaps better known as Uruk (the home of the legendary Gilgamesh) located approximately 100 miles southeast of Babel. Accad (or Akkad), understood to be located north of Babel, was the capital of the Akkadian Empire (Mesopotamia). The language of the Semitic Assyrians and Babylonians is known as Akkadian. Little is known about Calneh as it does not appear in any of the Akkadian inscriptions. The land of Shinar is a name that is generally accepted as a synonym for Babylon, also a reference for the area around Babylon.

To start the next phase of building his empire, Nimrod went into Assyria and built Nineveh, another name that readers should be familiar with from the story of Jonah. Nineveh was located on the Tigris River approximately 250 miles northwest of Babylon. Rehoboth-Ir was just outside of Nineveh and is considered by most scholars as a suburb of Nineveh. Calah was located approximately 18 miles south of Nineveh, also on the Tigris. As noted the city of Resen was located between Nineveh and Calah, the reference to being a great city refers to all four of these cities being essentially one large metropolis.

10:13 Egypt fathered Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim, 14 Pathrusim, Casluhim (from whom the Philistines came), and Caphtorim.

Egypt fathered seven sons, each name listed here is in the plural form (Hebrew ‘im’ ending). Ludim is often associated with Lydia in North Africa, the Bible also connects them to Cush and Put (see Jeremiah 46:9 and Ezekiel 30:5, Lud would be the singular form of the name). Anamim is connected to Cyrene and Lehabim was not too far away being in the vicinity near Egypt and Libya. Naphtuhim settled in the Delta Region in Lower Egypt and are often considered the people of Memphis. The Pathrusim went to Upper Egypt to the area known as the land of the Pathros. Casluhim, as noted, is where the future enemies of Israel, the Philistines, will come from. They settled on the coastal region of the Mediterranean between Egypt and Canaan. The Casluhim are also closely connected to the next son, Caphtor (see Jeremiah 47:4 and Amos 9:7). The Caphtorim were also known as the Kaptara who are believed to be connected with the island of Crete.

10:15 Canaan fathered Sidon his firstborn and Heth,

Canaan had a large family, having eleven sons and an unspecified number of daughters. His eldest son was Sidon who settled in the land of the Sidonians, he is also considered by some to be the progenitor of the Phoenicians. Heth was the father of the Hittites who originally were in the land of Canaan (see Genesis 15:19-21). After the fall of the Hittite Empire, it is believed that they migrated to the Far East and became known as the Cathay, who are associated with the people and region around Hong Kong. Apparently, some remnants of the Hittites stayed behind in the hill country of northern Judah (see Numbers 13:29).

10:16 and the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, 17 the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, 18 the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites. Afterward the clans of the Canaanites dispersed.

The next nine sons of Canaan may sound familiar to many readers as they are often listed in part or together, being the occupants of the Promised Land before the Israelites arrived. The Jebusites were the descendants of Jebus and occupied the city of Jerusalem for many years (see Joshua 15:63), although most scholars agree they were probably not the original inhabitants of the city. The Amorites occupied the hill country of Judah (see Numbers 13:29; Deuteronomy 1:44; Joshua 11:3) and portions of the east side of the Jordan River (see Numbers 21:13; Deuteronomy 1:3-7; Joshua 2:10; 9:10; 24:8; Judges 10:8; 11:22). Even though the Girgashites appear often in the Bible, the exact locations of their cities are not known. Some scholars have associated them with the Gerasenes listed in the New Testament (see Luke 8:26-39), which would place them in the area near the Sea of Galilee.

The Hivites occupied the central region of the hill country in Judah, including the city of Gibeon (see Joshua 9:3-7, 17; 11:19). Modern archaeology has connected them to several sites between Sidon and Jerusalem. The Arkites apparently occupied several cities in the Lebanon area including the ancient port city of Arva (also known as Sumra). The Sinites were also known as the Siyanru found in ancient texts, they formed a large coastal city between Ugarit (northern Syria) and Arvad (also Arwad, a small island off the coast of Syria). There are some scholars that connect the Sinites to the wilderness of Sin, Mount Sinai, and Sinim (being the Chinese ‘Siang’, making a possible Chinese connection).

The Arvadites were also known as the Ruad (in Assyrian and Egyptian literature) and the Arwada (in the Armana Letters) they are associated with the island Arvad (see paragraph above) and are connected to the people of the city of Tyre (see Ezekiel 27:1-9). The Zemarites were called the Tzimira in Assyrian inscriptions and are believed to have settled near the mouth of the Eleutheros River. The Hamathities are associated with Hamath, a city on the Orontes River in Syria.

10:19 And the territory of the Canaanites extended from Sidon in the direction of Gerar as far as Gaza, and in the direction of Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha. 20 These are the sons of Ham, by their clans, their languages, their lands, and their nations.

The text describes the basic border of the Canaanite territory. Sidon on the northwestern coast, south towards Gerar to Gaza on the southwestern coast, then southeast towards Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboiim to Lasha (exact location is not known today, possibly on the east side of the Dead Sea). The whole region took on the name of Canaan.

The record of Ham’s descendants is summarized in the same fashion that Japheth’s record was concluded. The references to their languages and dispersement are a strong indication that this section was written after the events of the next chapter as up to the Tower of Babel, especially since that event started while everyone was speaking the same language.

Considerations

Ancient Jewish Writings

Since the Jerusalem Targum was quoted above and that some of you might be wondering what a Targum is, this would be a good time to introduce you to some of the early Hebrew writings. However, please understand, this will only be a brief survey of an otherwise rich and very extensive subject of ancient Jewish literature. For the purpose of this introduction, we will divide the earlier writings into three primary types:

1. Scripture

Hebrew Scriptures have many names: the Tanakh (Tenakh, Tenak or Tanach); the Mikra; and in Christian Bibles it is considered the Old Testament (for this introduction we will refer to it as the Tanakh). While the order of the books within the Tanakh may vary, it is commonly divided into three major divisions: the Torah (the law or ‘teaching’, also known as the books of Moses), the Nevi’im (the prophets) and the Ketuvim (the writings). Prior to the Torah being written by Moses, it was conveyed from generation to generation orally, which was often referred to as the “Oral Law” or “Oral Torah.”

The Torah is often divided into three categories:

For many centuries thousands of manuscripts, along with their inevitable variations, were written by a wide range of scribes and scholars. Many of the writings during the Talmudic period (estimated to be from 300 B.C. to 500 A.D.) were lost or destroyed (the Syrians during Maccabean revolt of 168 B.C. destroyed most of the manuscripts of the Tanakh). In the post-Talmudic period, there was a group of scribes that saw the need to create a systematic approach to sort out the available texts and develop a uniform and accurate account of what we call the Old Testament.

These scribes called themselves the Masoretes, derived from the word ‘masorah’, essentially meaning “that which has been transmitted.” They carefully examined the scrolls that remained and identified the variations and disagreements and accepted the text that was supported by most of the manuscripts. They also identified another concern, the issue of proper pronunciation of the written Hebrew. Due to fact that the early Hebrew writing only contained consonants (vowel sounds, accentuation, and melody when chanting the text, were handed down orally from generation to generation), they developed a system of written vowel points so that people could read and properly pronounce the words. In addition, they created a form of punctuation to show the reader where a sentence began and ended.

Since the Masoretes highly revered the Torah (they believed it was dictated directly to Moses by God), they would not edit the text and made all their changes in what scholars call marginal notes, thereby not effecting the text itself. When the Torah was read, the reader would read the notes instead of the text when applicable. There were also some other substitutes provided for what we might call today a “G Rating.” Manuscripts that contained Masoretic notations were deemed appropriate for only for personal study and could not be used for public reading of the Torah.

These manuscripts were in the format known as codices (or codex in the singular), they were written on both sides of parchment, which were then bound between two pieces of wood (like what we call a book today). The oldest extant codex containing Masoretic notations is called the Leningrad Codex (1008 A.D.) and is the source of the Hebrew text reproduced in the Biblia Hebraica (1937 A.D.) and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1977 A.D.) However, the Mikraot Gelolot or “Great Scriptures,” which is often called the Rabbinic Bible, first published in 1516-1517 A.D. is considered the official Masoretic text and served as the Old Testament text for the King James Version (KJV).

2. Rabbinic Literature

Starting with the Mishnah (from the Hebrew essentially meaning “to study by repetition”), this is considered the first major work that attempted to compile the Jewish oral traditions around the beginning of the third century A.D. The Mishnah, as well as most of the rabbinic literature, are compiled from a variety of several tractates (a formal written work that is systematically analyzed and presented, essentially a synonym for a treatise) of legal opinions and debates. The Mishnah is divided into six ‘orders’ referred to as:

The Tosefta (Hebrew meaning ‘addition’) is considered as a supplement to the Mishnah (although approximately four times larger than the Mishnah).[16] While it contains the same six orders and mirrors much of the Mishnah, there are several sections that are significantly different.

The next series of rabbinic writings are the Talmuds (from the Hebrew meaning ‘study’, ‘learning’ or ‘instruction’), these are identified as the Jerusalem Talmud (believed to be written around 450 A.D.), which is also known as the Palestinian Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud (estimated to be written around 600 A.D.) The Jerusalem Talmud is a compilation of teachings and analysis of the Mishnah primarily of the schools of Tiberias, Sepphoris, and Caesarea (academies in Galilee area) that were transmitted orally for centuries prior to its compilation by Jewish scholars in the land of Israel. The general term 'Talmud' by itself is usually a reference to the collection of writings named specifically the Babylonian Talmud, referring to the post-biblical periods during which the Talmud was being compiled. This Talmud includes the teachings of the Talmudic academies and the Babylonian exilarchate (the leader of those that were being held captive in Babylon). The name is a reference to the period of captivity and was used long after the captivity was over. The Talmud has two basic components: the Mishnah (discussed above) and the Gemara (Hebrew meaning ‘completion’, is a clarification of the Mishnah and related writings). The Talmud consists of 63 tractates containing the teachings and opinions of thousands of rabbis on a variety of subjects, including the Halakha (Hebrew essentially meaning “the way to behave”), Jewish ethics, philosophy, customs, and history. The Babylonian Talmud is considered the basis for all Jewish customs and law.

A Targum is a name given to a translation, paraphrase, or interpretation of ancient texts (Tanakh, Midrash, etc.) written in Aramaic for the purpose of teaching or explaining to those unfamiliar with the Hebrew language. Initially it was prohibited to write down a targum, however, several targumatic writings started to appear by the middle of the first century as the use of Hebrew began to decline. Many targums were elevated and made authoritative by several rabbis and other Jewish leaders. Some of those authoritative Targums to note are the:

There are several rabbis that have contributed to the various Talmudic and post-Talmudic literature, however there is one rabbi that seems to stand unique and highly revered among rabbis, and that is Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (who is also known as Maimonides and RaMBaM), an astronomer, physician, and philosopher (unsure of exact date of birth, possibly 1136, died on December 12, 1204). Maimonides offered commentary on a wide variety of subjects including the Torah, the largest work being simply known as the Mishneh Torah, meaning the “Repetition of the Torah.” Which should not be confused with the Mishnah (in English note the use of an ‘e’ instead of an ‘a’).

3. Commentary

The third category of ancient Hebrew writings are known as the Midrash, a compilation of several commentaries and interpretations that expound the Scriptures (Tanakh) and occasionally the Mishnah. Like the Talmud, the Midrash is also divided into two categories. Halaka (or halacha) referring to religious practices (see above regarding the Talmuds) and Aggadah (Hebrew meaning 'telling'), which includes interpreting Biblical narrative, exploring questions of ethics and theology, basically anything that is not halakhic falls into this category.

Summary

Again, this is a quick and a very non-exhaustive review of ancient Hebrew literature. One question that many of you might be thinking is, “Why is the subject of ancient Hebrew literature of any interest to a Christian?” Regarding Old Testament Scripture, it should be obvious, since God is the ultimate author (as pointed out earlier in the first Bible study tip), He is indeed the creator of language, no human author can compare. Plus, the subject is important, meaning that through the Old Testament we learn about God, His Character, His rules and regulations, His priorities and what is important in life (yes, that’s right, the meaning of life). The Old Testament also clearly demonstrated the need for a Savior, since mankind cannot fix the problem of sin. Plus, we learn from the Old Testament the history and importance of the Hebrew people, the Israelites and the Jews (all names for the same people group). Through that history we can understand the many customs found in the New Testament.

Jacob Neusner, an author of several books and a leading authority in Rabbinic literature and Judaism, wrote the following regarding reasons why a Christian might want to understand Rabbinic literature:

But outside of the community of Judaism the greatest interest in Rabbinic literature derives from the various Christian communities, Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox, for three closely related reasons.

First, Christians find in Rabbinic Judaism traditions and rules that clearly exercised authority in the time of Jesus, as attested by the Gospels and the Letters of Paul. Rabbinic literature clarifies convictions and practices that enter into the Gospel narratives and Paul’s doctrines. So Rabbinic Judaism affords access to background material that is taken for granted in accounts of Christians origins. Knowing the background material sheds light on the context of early Christians writings.

Second, Christians wonder why the majority of Jews from antiquity to the present day have affirmed a view of Scripture and its imperatives different from the Christian one. That puzzlement takes the form of the question, “Why not?”—meaning, why did “the Jews” viewed as a corporate entity not “accept Christ” and join Christianity? Christians understand that Rabbinic Judaism from antiquity to the present day formulated the alternative to Christianity. It is this opinion that most Jews through the ages have affirmed, in preference to Christianity (and Islam). In the canonical writings of the Rabbinic sages is the affirmative answer to the negative question, “Why not?”

Third, in combination, these two reasons for Christian interest in Rabbinic literature—materials for the Judaic exegesis of the Gospels, and accounts of the Judaic alternative to the Christian reading of the Scriptures shared by Judaism and Christianity—produce a third reason for both Christian interest in Rabbinic literature and Judaic interest in Christian literature. Rabbinic literature affords perspective on Christianity (particularly biblical Christianity, orthodox and catholic) by affording materials for comparison and contrast.

Nothing so illuminates what people do than knowledge of what they have chosen not to do. Rabbinic literature affords a source for alternatives to the Christian way—both alternative modes of expressing doctrines and laws held in common—and different views of issues faced by both communities of Scripture.

This is a two-way street. For the same reason that students of earliest Christianity gain perspective from the Rabbinic literature, so students of formative Judaism grasp matters more clearly in light of Christian alternatives, both rhetoric (form) and in proposition.[17]

The story of Jonah and the great fish is well known by most people, even if they never read the Bible. The prophet Jonah is often given a bad reputation due to his reluctance to serve God. But there is much more going on in that brief four-chapter book in the Bible bearing his name. First, Nineveh was the capital city of the Assyrian empire, an enemy of the nation of Israel. Secondly, most scholars believe that Jonah was being a good patriot and really did not want God to bless the Assyrians.

However, based on the fact that the Assyrians were not God’s people, nor were they related in any way to the nation of Israel, the question that is often asked is why did God demand obedience with this otherwise pagan nation? There may be several reasons why. To begin with, it was a very wicked city, Jonah was instructed by God to, “Get up and go to the great city of Nineveh. Announce my judgment against it because I have seen how wicked its people are.” (Jonah 1:2, NLT) God knew what was going on and cruelty, evil, sorcery, wickedness, and pride will not be tolerated by God, in any nation. We know that years later the city returned to its old ways, as described in the book of Nahum, “Horsemen charging, flashing sword and glittering spear, hosts of slain, heaps of corpses, dead bodies without end—they stumble over the bodies! And all for the countless whorings of the prostitute, graceful and of deadly charms, who betrays nations with her whorings, and peoples with her charms.” (Nahum 3:3-4) Archaeology fully supports all these claims, including a level of cruelty beyond imagination. Perhaps that is why God spoke through the prophet Nahum, “Nothing can heal you; your wound is fatal. All who hear the news about you clap their hands at your fall, for who has not felt your endless cruelty?” (Nahum 3:19, NIV) Jonah knew what type of people the Assyrians were, perhaps he did not want them to repent of their sins. But one thing we can see in the book of Jonah, no matter how bad someone has sinned, God can still have an effect on them and change them. When Jonah warned the Assyrian king, he listened, and the nation repented. So don’t stop praying for others and for fallen nations!

The Sons of Shem

10:21 To Shem also, the father of all the children of Eber, the elder brother of Japheth, children were born.

The line of Shem will be the recipients of many great promises. Through Shem will come the Messiah (see Genesis 3:15) and the fulfillment of Noah’s prophecy, “Blessed be the LORD, the God of Shem; and let Canaan be his servant. May God enlarge Japheth, and let him dwell in the tents of Shem, and let Canaan be his servant.” (Genesis 9:26-27) There is much debate as to why the author chose to reference Eber, the great-grandson of Shem in this verse. But since it is considered a Hebrew custom to mention the name of the greatest, or at least the most recognized, name when describing or referencing a person’s lineage; many scholars believe that the children of Eber were well known. The name of the Hebrew people is believed to have been derived from the word ‘Eber’ (Hebrew meaning “on the other side” or to “crossover”). Abram, before his name was changed to Abraham, was first to be called a Hebrew in Genesis 14:13.

10:22 The sons of Shem: Elam, Asshur, Arpachshad, Lud, and Aram.

Shem had five sons, Elam, Asshur, Arpachshad (or Arphaxad), Lud, and Aram. Elam was the progenitor of the Elamites who later joined the Medes to form the Persian-Mede Empire. The family of Asshur are considered to be the founders of the Assyrians. Nimrod (see above under Ham) would later invade Asshur where he would build the city of Nineveh. Arpachshad remains somewhat a mystery, however his family was chosen to continue the line leading to Abraham and of course the Messiah. There is a city north of Assyria in the Armenian region known as Arrapachitis believed to be named after Arpachshad, but most scholars disagree with that origin. Some scholars connect Arpachshad to the city of Ur, the home of Abram. Lud is believed to be the ancestor of the Lydians. The fifth son of Shem was Aram, the father of the Arameans (or Aramaeans), a sizable nation whose language (Aramaic) was adopted as the primary language of many great nations including Assyria and Babylonia. It was the prominent language spoken during the time of Christ. Many readers of the Bible may not be aware of the fact that the Bible contains many passages originally written in Aramaic, including sizable portions of Daniel and Ezra, as well as a verse in Jeremiah and a word in Genesis (many suggest some other words in Genesis, Numbers, Job, and Psalms as the language is very similar to Hebrew).

10:23 The sons of Aram: Uz, Hul, Gether, and Mash. 24 Arpachshad fathered Shelah; and Shelah fathered Eber.

The author then lists the sons of Aram and Arpachshad, but there is no mention regarding the sons of Elam, Asshur, or Lud. Uz is often associated with a region in or near Arabia that later became Job’s homeland (see Job 1:1 and Jeremiah 25:20), however some believe he settled in northwest Mesopotamia (see Genesis 22:21). The settlement locations of the last three names Hul, Gether, and Mash (the Septuagint and 1 Chronicles 1:17 refer to Meshech), are largely unknown. Arpachshad is listed as having only one son, Shelah, who gave birth to Eber (see above). The Septuagint places the name Kenan (or Kainan) in the text between Arpachshad and Shelah as it is presented in Luke 3:35-36. It appears that the Masoretic Hebrew Text omitted this generation.

10:25 To Eber were born two sons: the name of the one was Peleg, for in his days the earth was divided, and his brother’s name was Joktan.

Eber had two sons, Peleg and Joktan. The phrase “the days the earth was divided” is the source of some debate, however most scholars believe that it is a reference to the language division brought on as the result of the Tower of Babel incident when God confused the people’s language and dispersed them around the world (see Genesis 11:1-11). Nimrod would have been near the same age as Eber (same generation). Some relate Peleg’s name, which is believed to mean “water channel” or “to divide,” as being the time when the world’s continents shifted. There are a few scholars that connect Peleg to the Palasgians, others prefer a connection to the ancient city of Palga near the Harbur River.

10:26 Joktan fathered Almodad, Sheleph, Hazarmaveth, Jerah, 27 Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah, 28 Obal, Abimael, Sheba, 29 Ophir, Havilah, and Jobab; all these were the sons of Joktan. 30 The territory in which they lived extended from Mesha in the direction of Sephar to the hill country of the east.

These five verses list thirteen sons of Joktan, it appears that they all settled in Arabia. Ophir is often associated with a location where gold is found (see 1 Kings 9:28; 10:11; 22:48; 1 Chronicles 29:4; 2 Chronicles 9:10; Job 22:24; 28:16; Psalms 45:9 and Isaiah 13:12). The son named Sheba is different than one above listed as the grandson of Cush as well as another named Sheba later in Genesis 25:3. This Sheba is believed to be associated with the Sabeans. Their territory extended from Mesha (possibly Massa, see Genesis 25:14, the western border) towards Sephar (eastward) to the mountains.

10:31 These are the sons of Shem, by their clans, their languages, their lands, and their nations.

In the same manner reported for Japheth and Ham (see above), this summary points out that they lived in distinct clans with their distinct languages in their lands and nations.

10:32 These are the clans of the sons of Noah, according to their genealogies, in their nations, and from these the nations spread abroad on the earth after the flood.

This concludes the section on the sons of Noah for a total of 70 families listed, providing a transition to the next section regarding the Tower of Babel and the disbursement. The phrase “these the nations spread abroad on the earth after the flood,” is a reminder that all people from the days of the flood to our current day, are descendants of Noah.

Considerations

No word for grandson or granddaughter

In the Hebrew language the word ‘bēn’ generally means ‘son’, however it can also refer to other descendants such as a grandson or any other male offspring, since there is no prefix or word to describe a grandson or great-grandson. As pointed out above under the commentary for verse 21, it is a custom to mention the name of the most recognized name in a family’s lineage. For example, Jesus was called the “Son of David,” even though He was not David’s direct son. We also know that this phrase was a Messianic title, since the promised Messiah would be a descendant of King David (meaning that those people calling Jesus the “Son of David,” were technically calling Him the Messiah, the Christ, which is why the Pharisees were so upset with them). The same applies for daughters (Hebrew word ‘bat’).

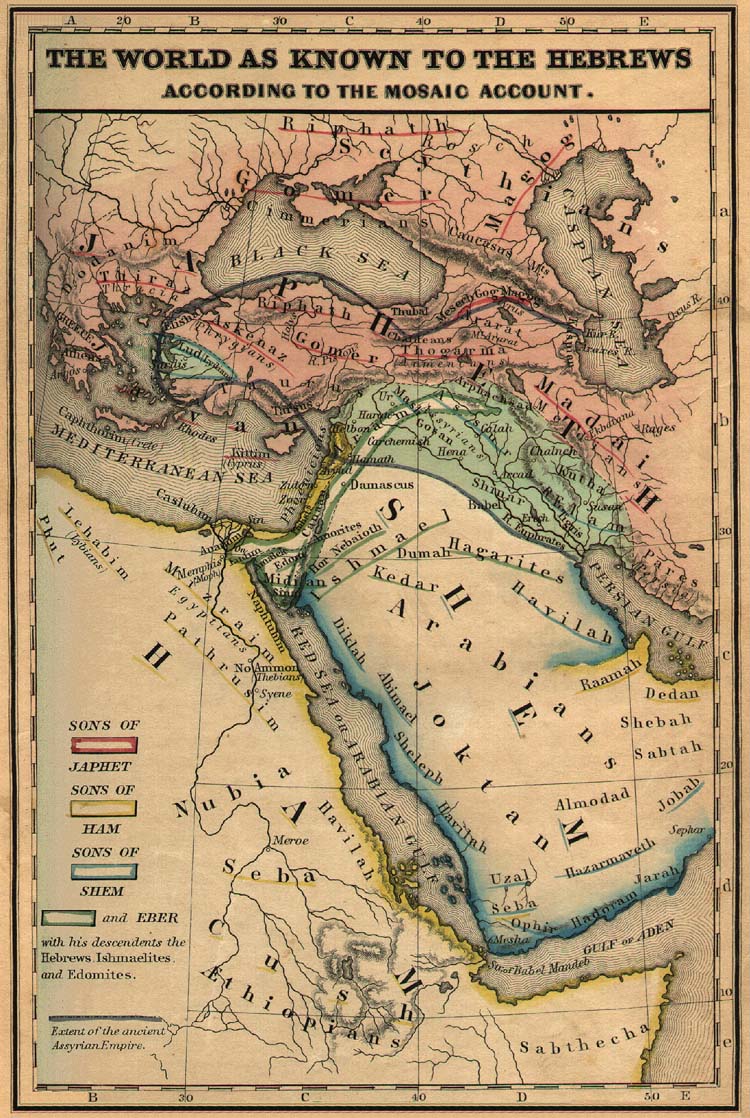

Map Based on Genesis Chapter Ten [18]

⇐Previous Chapter (Introduction/Index) Next Chapter⇒

[1] Poole, M. (1853). Annotations upon the Holy Bible (Vol. 1, p. 26). New York: Robert Carter and Brothers.

[2] Herodotus. (1920). Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. (A. D. Godley, Ed.). Medford, MA: Harvard University Press.

[3] Fruchtenbaum, A. G. (2008). Ariel’s Bible commentary: the book of Genesis (1st ed., p. 207). San Antonio, TX: Ariel Ministries.

[4] Josephus, F., & Whiston, W. (1987). The works of Josephus: complete and unabridged (p. 36). Peabody: Hendrickson.

[5] Fruchtenbaum, A. G. (2008). Ariel’s Bible commentary: the book of Genesis (1st ed., p. 207). San Antonio, TX: Ariel Ministries.

[6] Fruchtenbaum, A. G. (2008). Ariel’s Bible commentary: the book of Genesis (1st ed., p. 207). San Antonio, TX: Ariel Ministries.

[7] Josephus, F., & Whiston, W. (1987). The works of Josephus: complete and unabridged (p. 36). Peabody: Hendrickson.

[8] Fruchtenbaum, A. G. (2008). Ariel’s Bible commentary: the book of Genesis (1st ed., p. 209). San Antonio, TX: Ariel Ministries.

[9] Strong’s Hebrew 1471.

[10] Mark, J. J. (2009, September 2). Sea Peoples. Retrieved January 17, 2018, from https://www.ancient.eu/Sea_Peoples/

[11] Fruchtenbaum, A. G. (2008). Ariel’s Bible commentary: the book of Genesis (1st ed., p. 211). San Antonio, TX: Ariel Ministries.

[12] Yamauchi, E. (1999). 622 חֲוִילָה. R. L. Harris, G. L. Archer Jr., & B. K. Waltke (Eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (electronic ed., p. 269). Chicago: Moody Press.

[13] Fruchtenbaum, A. G. (2008). Ariel’s Bible commentary: the book of Genesis (1st ed., p. 213). San Antonio, TX: Ariel Ministries.

[14] Etheridge, J. W. (Trans.). (1862–1865). The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch; With the Fragments of the Jerusalem Targum: From the Chaldee (Ge 10). London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.; Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green.

[15] Mishnah. (2018, January 29). Retrieved January 29, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mishnah

[16] Eisenberg, R. L. (2004). The JPS guide to Jewish traditions (1st ed., p. 501). Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society.

[17] Neusner, J. (2005). Rabbinic literature: an essential guide. (pp. 4-5) Nashville: Abingdon Press.

[18] The World as Known to the Hebrews (map) - Classic BLB Images. Retrieved from https://www.blueletterbible.org/images/blb_classics/imageDisplay/world_b